September 17, 2024

Beethoven’s Fidelio: Reaching toward the light

Fidelio, Beethoven’s only opera, is an opera like no other. A drama of ideas that makes deeply moving theater out of abstractions, it never ceases to move audiences — especially, perhaps, in times of political tumult — with its vision of freedom secured through struggle, love, and hope. Originally titled Leonore: or The Triumph of Conjugal Love, it is ultimately based on a French libretto by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, which had been set as an opera by two other composers before Beethoven; it was prepared for his purposes by Joseph Sonnleithner. Its original premiere was in 1805, but revisions were made by Beethoven’s friend Stephan von Breuning in 1806, shortening the opera from three to two acts. After further revisions to the libretto by Georg Friedrich Treitschke, along with many revisions to the musical score, the opera opened again in 1814. Although the earlier versions exist and have their defenders, it is almost always the 1814 version (by convention the only one called Fidelio) that we hear today.

Beethoven wrote four overtures for the opera. The one standardly played today is the brief overture known as the Fidelio Overture. The larger symphonic works known today as Leonore no. 2 and Leonore no. 3 are usually thought too lengthy for overture performance. However Gustav Mahler, who greatly admired Leonore no. 3, conducted it between the end of the prison scene and the finale, and other conductors have sometimes followed this idea. Today the inclusion of the lengthy overture (about sixteen minutes) is generally considered too great a distraction from the drama’s onward movement; Lyric will not perform it.

Beethoven found the whole business of opera difficult, particularly in light of his advancing deafness, which made teamwork a chore. Thus, though he never stopped looking for suitable opera libretti, he never completed another opera. The magnificent one he did complete must suffice. Let us turn, then, to its mysteries and complexities.

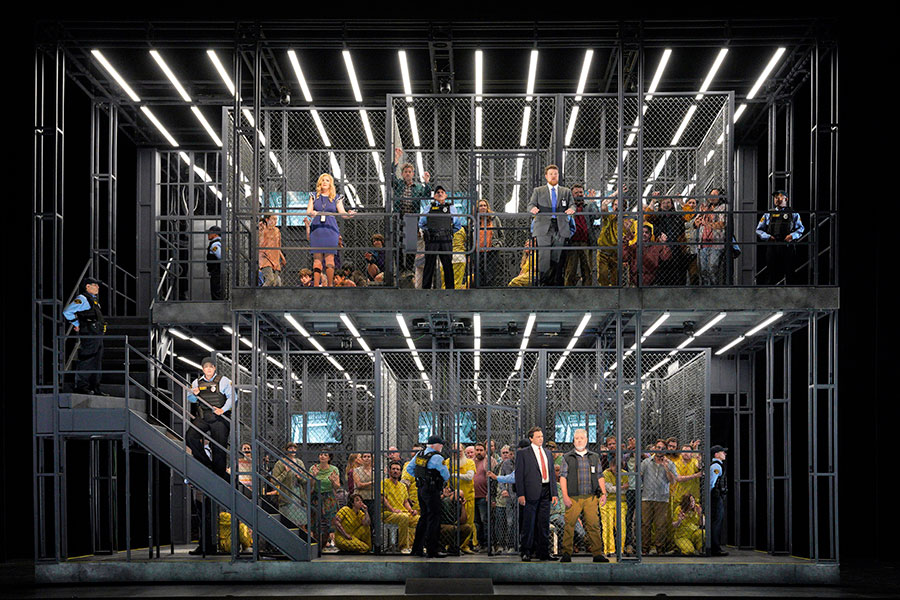

The company of San Francisco Opera's production of Fidelio.

Fidelio poses three puzzles for its interpreters. The first, and the most hotly debated, is the relationship between its two acts, and whether the discontinuity we experience is a flaw or part of Beethoven’s intention. The opera, it seems, begins as a romantic/domestic comedy and ends as a heroic drama of ideas. There is no doubt that the relationship between the acts gave Beethoven difficulty and was a major source of his revisions of 1814, which cut a lot of dialogue and slimmed down the psychology of the romantic comedy. Occasionally this has been offered as a reason to perform the 1805 or 1806 versions rather than the one we usually hear. The 1805 version is a worthy work in its own right and worth occasional performance. Usually, however, and I think rightly, the 1814 version is preferred on grounds of its moving depiction of the struggle for freedom. This is the core of Beethoven, and he was never comfortable with the genre of domestic comedy, particularly when it involved erotic relationships. (He said that Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro was an ignoble work.)

The opera, however, is consistent in its discontinuities. What we ought to say, indeed, is that Fidelio is all about discontinuity — how mundane life can offer moments of breakthrough, in which ordinary people ascend to the sublime. Some of these moments are indeed in Act II: Leonore’s realization that she wants to help the prisoner, no matter who he is; the sacramental moment in which Rocco and Leonore offer the prisoner bread and wine; the famous trumpet call; the ecstatic duet; and the entirety of the finale, in which the entire people join in praising justice triumphant. But Act I already shows daily life as, so to speak, porous, offering moments of egress from the mundane world to some type of deeper or higher spirituality. One of these is the four-part canon that begins with Marzelline’s words, “Mir ist so wunderbar” (“I am struck with wonder”), in which the characters step aside from their daily activities into hushed reflections. We feel that something of a different nature is happening here: people are becoming thoughtful, even spiritual. Noting the parallel with the sacramental moment of Act II, some interpreters hold, plausibly, that the canon is also sacramental — its topic being marriage, a sacrament to which Beethoven attached great value. The opera, after all, is about the triumph of marital love. In its moments of profound moral and spiritual commitment, daily life is penetrated by something more than daily.

Furthermore, the moral core of the entire work is in Act I: the Prisoners’ Chorus, which has no role in the plot and therefore must be there in order to express an idea of human freedom. We don’t know who these prisoners are — whether they are all political prisoners like Florestan or whether many of them are common criminals. We do know that they are treated badly, ill nourished, not allowed fresh air and outdoor movement. As they feel the unaccustomed air on their faces and turn toward the sun, they sing, “Oh what joy! In the free air to breathe with ease! Only here, only here is life!” On the word “air” they move to their highest note, and the harmony shifts to what critic Paul Robinson rightly calls “an exalted subdominant — a move that becomes practically a harmonic code for the idea of freedom in the opera.” Beethoven impresses this phrase on each listener’s mind. (And we can’t help thinking about the connection between breath and singing: the conditions of opera itself involve a freedom that is all too often denied.) Next a single prisoner steps forward: “With trust we will build on God’s help. Hope whispers gently to me: we shall be free, we shall find rest.” Again the melodic line arcs upward, illustrating the idea of aspiration; and the word “free” occupies the highest note. All too soon, this brief window onto something wonderful begins to close: “Speak softly, restrain yourselves. We are observed by ears and eyes.” The beauty of freedom is shown as much by the pathos of its denial as by the beauty of its momentary sighting. The discontinuity between freedom and the prison, between ordinary life and its hopeful transcendence, between going along as usual and moments of vertiginous ascent, is the real theme of Fidelio: doors opening and closing, surprising bursts of light.

Fidelio’s second puzzle has been its politics: What idea of justice, or the just society, does its text and music embody? It is all so terribly abstract. Much has been written to little purpose about whether Beethoven liked or disliked the French Revolution. This is a pretty useless question, since one might easily love the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen while detesting the Terror, and there were many stopping points along the way from the former to the latter — one of those being the point chosen by the leaders of the American Revolution, which of course was also part of Beethoven’s mental context. What Beethoven puts into his opera is what he wanted us to know: that the arbitrary, lawless tyranny of some human beings over others is always wrong; that those who blow the whistle on crimes, as did Florestan, must be protected from the vengeance of those on whom they inform; that a prison system that deprives its inmates of fresh air and movement is horrible; and that the deliberate starvation of a prisoner is even more horrible. More generally, that human beings should be protected in their freedom to breathe and use their voices (Enlightenment freedoms of expression, association, and of the press are essential supports for that idea). In making Leonore the linchpin of the plot, the opera also insists strongly on the agency of ordinary people in bringing about political change. It thus has a democratic element.

Beyond this, the work is compatible — and is intended to be compatible — with many accounts of political authority, from constitutional monarchy to law-governed and not minority-oppressive democracy, and it is no surprise that it has been staged to great emotion at many different moments when the yoke of arbitrary power has been thrown off, notably at the reopening of many German opera houses after the defeat of the Nazis. One might object that Fidelio was also performed under the Nazi regime. Thomas Mann wrote from exile, “What obtuseness it took to listen to Fidelio in Himmler’s Germany without covering one’s face and fleeing the hall.” But conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler replied in a letter to Mann, “Fidelio never has been presented in the Germany of Himmler, only in a Germany raped by Himmler.” In other words, performing the opera was the ultimate anti-Nazi gesture, reminding everyone of the noblest values of German culture that the Nazis had suppressed. The opera is a call to conscience for audiences wherever it is performed, whether in pretty good or pretty horrible regimes.

The work’s third puzzle is its sudden happy ending. The famous offstage trumpet call initiates an abrupt reversal in the fates of all the characters. Leonore has already foiled Pizzaro temporarily, but she succeeds only because of an event so unexpected, so almost random, that the characters would hardly be justified in relying on such an event for their future happiness. When Leonore and Florestan embrace in the duet “O namenlose Freude” (“Oh nameless joy”), their music is appropriately feverish, cascading upward with no secure basis, striving at the limits of their vocal range, with no stable confidence, with words suggesting that words have given out (“nameless” joy, “unnameable woes,” “overlarge pleasure”). The finale itself is more sedate, in the confident key of C major. Everyone joins the final chorus, and the King’s messenger seems to be all that could be wanted, although we have absolutely no idea who this monarch is or what his regime is like. Justice is done, the villain punished, Florestan unchained.

Elza van den Heever and Russell Thomas in Fidelio.

And yet: what are we really to make of this fairy tale, this sudden exaltation? It is a moment, an Augenblick. And human lives do contain surprising moments of wonder and joy. But that very word, Augenblick, so often repeated in the opera (as Joseph Kerman reminds us in an insightful article), can’t help reminding us that Pizzaro too has his moment: his aria of sadistic revenge begins“Welch’ein Augenblick” (“What a moment”), and he repeats the word later, in the dungeon, when he is about to murder Florestan. When Leonore, asked to unchain Florestan, repeats the phrase, saying “O welch’ein Augenblick,” what are we to make of this repetition?

Beethoven, like his audience, knew all too well that in real life politics is dizzyingly unstable. A promising beginning can all too quickly turn oppressive — as the early days of the French Revolution, with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, was followed by the arbitrary cruelty of the Terror, and as the early days of Napoleon the liberal lawgiver, once the hero of Beethoven’s Third Symphony, were followed by Napoleon the Emperor, at which point Beethoven is said to have withdrawn his dedication and titled the symphony simply “Eroica” with no real-life dedicatee. The play on the word Augenblick is surely a sign that we are meant to see the victory of the good as insecure and temporary, as in life it always must be. (At the end of the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill Threepenny Opera, the hero is rescued by the King’s order, delivered by a messenger on horseback — a satirical reference to Fidelio, I am certain — at which point Mrs. Peachum says, “Life would be so easy and peaceful, if King’s messengers always came riding in.”)

A famous semi-staged version of Fidelio conducted by Daniel Barenboim in Chicago in 1998 contained added narration written by Edward Said — spoken by Waltraut Meier, who played Leonore, as if Leonore is looking back from many years later, meditating on the fact that things did not work out as she wished. This might initially seem like intrusive Regietheater, but in fact Said has written an excellent article on the opera arguing for just this sense of vulnerability and impermanence as built into its music, and I believe he is right, though perhaps too pessimistic in the conclusion he draws. Yes, power is unreliable, regimes are unreliable. We can’t count on messengers who turn up at just the right moment. What we can nonetheless love and regard with awe is the struggle of courageous human beings who refuse the easy option of despair, who strive for the right against great odds, a struggle that is beautiful in itself, whether it ultimately prevails or not. Beethoven’s music for Leonore and Florestan brilliantly depicts this difficult upward struggle.

What propels that struggle is hope, and Fidelio is opera’s greatest musical depiction of that emotion. Hope is slippery. It does not track the probabilities: if your loved one is very ill, you can hope even when the situation is grave; you can also abandon hope when things are going somewhat better. Hope is a way of seeing a situation, as, so to speak, half-full rather than half-empty, and it is of crucial importance for action. People of hope will strive and struggle; without hope people will put up with the worst and do nothing. Immanuel Kant, a leading thinker of the Enlightenment and a philosopher whom Beethoven greatly admired, said that all human beings had an obligation to cultivate hope in themselves, because we all ought to struggle for the good, and only hope can propel that struggle. That idea lies at the core of Fidelio.

The finale of Fidelio.

The key arias of both Leonore and Florestan are musical embodiments of hope. They are different. Hers moves from denunciation of Pizzaro into a gentle meditative invocation of hope, the legato phrase arcing upward. Then, when hope arrives in response to her call, she is propelled into action, and the music becomes rapid, decisive, and heroic, attempting the most difficult runs with seeming ease. In Florestan’s case, his aria’s meditative part is about his past, and he seems to have no path forward to action — and yet, suddenly, hope arrives in a fevered dream of Leonore, the vocal line leaping upward with unsteady and anxious thrusts. His hope, for the present, leads nowhere: he needs her actions to move forward.

The finale depicts justice arriving in response to the committed and courageous actions of good ordinary people. And it does not simply represent hope; it inspires it in its audiences, as unfailingly as its companion piece, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Asked by the King’s messenger to free her husband from his chains, Leonore does so, exclaiming “O welch’ein Augenblick” — quoting verbatim from Pizzaro but in the opposite moral sense. At this point there is a naked oboe solo that arcs gently upward (another “exalted subdominant”) and then descends as if to touch the formerly imprisoned man. Gentle and serene, the melody was borrowed by Beethoven from an earlier never-performed cantata, written in 1790 to honor the death of the enlightened Emperor Joseph II, in which it is sung to the words, “Now mankind reaches toward the light.” It has come to be called Beethoven’s Humanitätsmelodie, “melody of Humanity.”

Beethoven’s ending is perilous and temporary — and, I believe, intended to be heard as such. And yet it tells us that the struggle for justice is not futile, that there are “moments” — openings for decent people to struggle for change, and sometimes for a while to succeed, propelled by hope and love. There may be no solid reasons for hope, but hope is all we have to inspire us to fight for justice. And we must continue to fight because we can. We might call Fidelio Beethoven’s — and our own — Humanitätsoper, the opera of humanity, striving for the light.

Martha C. Nussbaum is Professor of Philosophy and Law at the University of Chicago. Her most recent books are Justice for Animals (2023) and The Tenderness of Silent Minds: Benjamin Britten and his War Requiem (2024).